Increasing possibility of a Sudden Stratospheric Warming in the New Year which may bring colder weather

Blog looking at the increasing probability from weather models for a Sudden Stratospheric Warming in early January, which could bring colder and wintry weather, especially if there is a split in the polar vortex following the SSW.

There is growing support for a possible Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) in early January, which could “load the dice” in favour of cold and wintry weather in northern Europe including the UK in the New Year.

A Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) occurs when the usual westerly flow over the arctic is disrupted by large-scale atmosphere waves (called Rossby waves) in the troposphere which get pushed higher into the atmosphere. These waves can “break” (like waves in the ocean) on top of the polar vortex and weaken it. If waves are strong enough, the winds of the polar vortex can weaken so much that they can reverse from being westerly to easterly. This leads to cold air descending and warming rapidly, with a sudden jump in temperature.

Evolution of SSW in January 2015. Image courtesy of Patrick Martineau

Although a Sudden Stratospheric Warming refers to a rapid warming (in extreme cases as much as 50°C in just a couple of days) in the polar stratosphere, between 10 km and 50 km up, a major SSW is often defined as a wintertime event in which the zonal (westerly) mean wind at 60N and 10 hPa reaches zero and turns easterly.

Most models predict that the polar vortex will remain slightly weaker than average for the rest of December, with some models indicating a full-on stratospheric polar vortex breakdown in early January. The two main NWP (Numerical Weather Prediction) models that will be looked in this blog, ECWMF and GFS, forecast the stratosphere winds and temperatures, but differ between them, for now, on the likelihood on a SSW.

If the sudden stratospheric warming does happen, the most likely time would be the first 10 days of January, with effects on the weather at the populated mid-latitudes of Europe and North America appearing a few weeks later.

December has so far seen a slightly weaker than average polar vortex, which makes it more susceptible over a prolonged period, to small wobbles that can further destabilize the vortex and break it down completely and this is what is being hinted at by the models in the next few weeks.

The 12z European ECMWF ensembles yesterday showed 29 out 51 ensembles (57%) with a U wind reversal at 60-90 N at the beginning of January. The zonal wind reversal is where westerly winds at 10 hPa reverse direction to easterly, while stratosphere temperatures rise.

Meanwhile, the USA’s NOAA GFS has also been trending towards an increasing likelihood of a SSW at times recently, but nowhere near as keen at ECMWF for now. The 00z GFS ensembles this morning have only 2 out of 30 of its ensembles, which includes the operational run, indicating a sudden stratospheric warming (SSW).

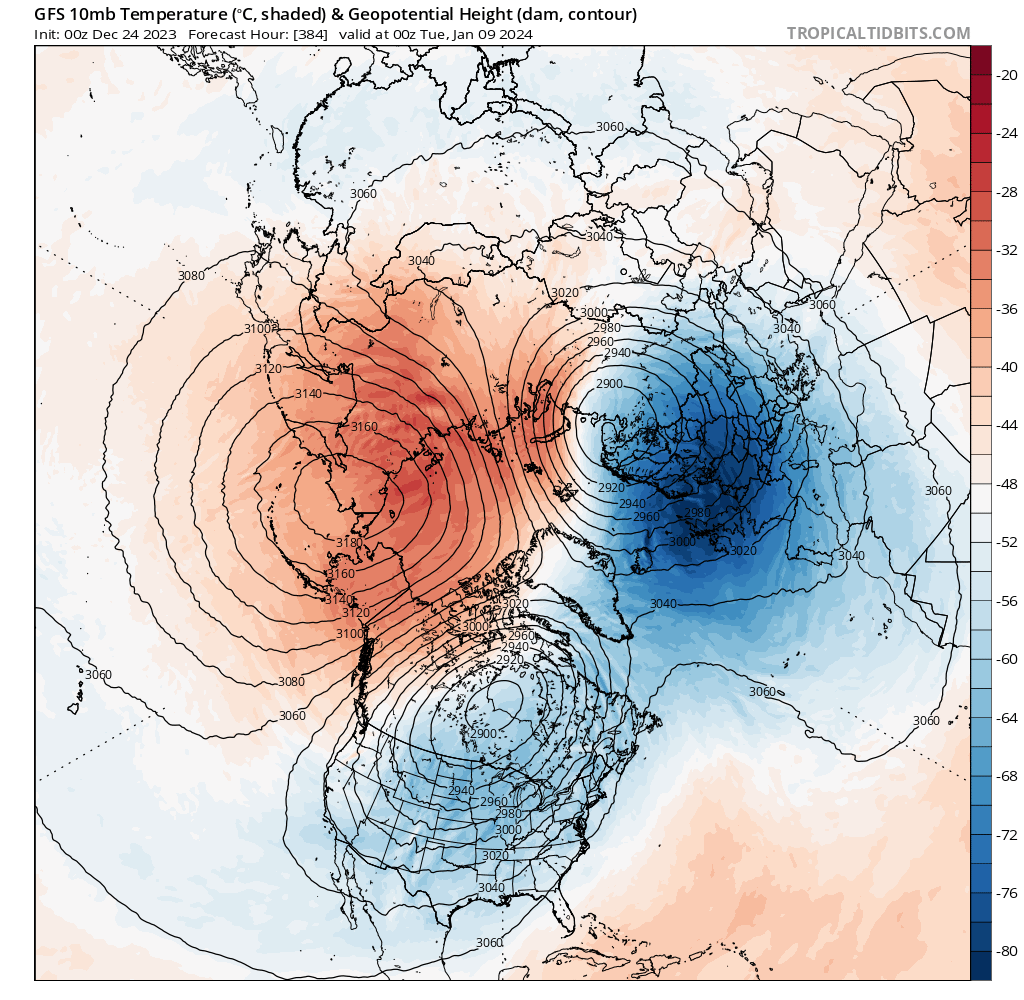

The 00z GFS operational run showed a split in the stratosphere polar vortex around the 9th January.

While the 00z EPS and GEFS mean do show the polar vortex splitting in the outer reaches of the run.

Following an SSW, the disrupted vortex in the stratosphere can couple with the troposphere (where our weather happens, with the easterly winds propagating downwards to the earth’s surface leading to a weakening of the polar jet stream leading to high latitude blocking high pressure and lower pressure over mid-latitudes, mirroring the stratosphere. This can lead to extreme winter weather, such as the extreme cold snap in late February / early March 2018, as cold air bottled up over the arctic escapes and causes cold air outbreaks over parts of Europe, parts of Asia, and the USA.

However, the downward propagation of the reversal of zonal winds and coupling of the stratosphere with the troposphere can take weeks or even months and impacts at the surface are not guaranteed and they are not necessarily experienced everywhere. Every SSW is different and around 66% of them lead to colder conditions, so not all SSW events lead to cold. Recent SSW events occurred in January of 2019, January of 2021 and February of 2023. Following the SSW on 1st January 2019, there was little impact on the weather for the UK and NW Europe as in bringing cold and wintry weather.

The major SSW in Feb 2018 did bring major impactful cold weather to the UK and Europe late in February and early March though. For that SSW, the reversal of winds (blue) can be seen mid Feb 2018 between 60N and 90N, with quick propagation downwards to the troposphere:

Yesterday's ECMWF weeklies 500 hPa update does hint at high latitude blocking high developong in January towards Iceland and Greenland, perhaps as a result of the SSW, but also could be the consequence of other drivers, such as the madden Julian Oscillation (MJO).

So if the SSW does occur in the New Year, which is looking increasingly likely, though not a certainty yet, then there is a strong chance that the UK and northern Europe could see some cold and wintry impacts later in January and perhaps over into February too. We'll keep you posted over the next few weeks on the potential for the SSW and if one happens, if there will be impacts from it on our weather with regards to colder and wintry prospects.